Bildnachweis: Dee – stock.adobe.com, R. Gygax and T. Meier.

Liquidation preference clauses are often a critical and disputed part of negotiation in funding agreements. We discuss the two basic types of “participating” and “non-participating” liquidation preferences and analyze whether distributions of exit proceeds, particularly at low exit value, are balanced between founders and investors.

Investment agreements frequently include a provision called liquidation preference to protect the cash invested and to guarantee preferred payout to investors at the time of an exit. They may apply particularly for a sale of the company or company wind-down, where residual cash is distributed to shareholders. Here we illustrate the two most common versions of liquidation preferences and their effect on the payout scheme for investors and founders with focus on low exit values/multiples.

Liquidation Preferences – the principle

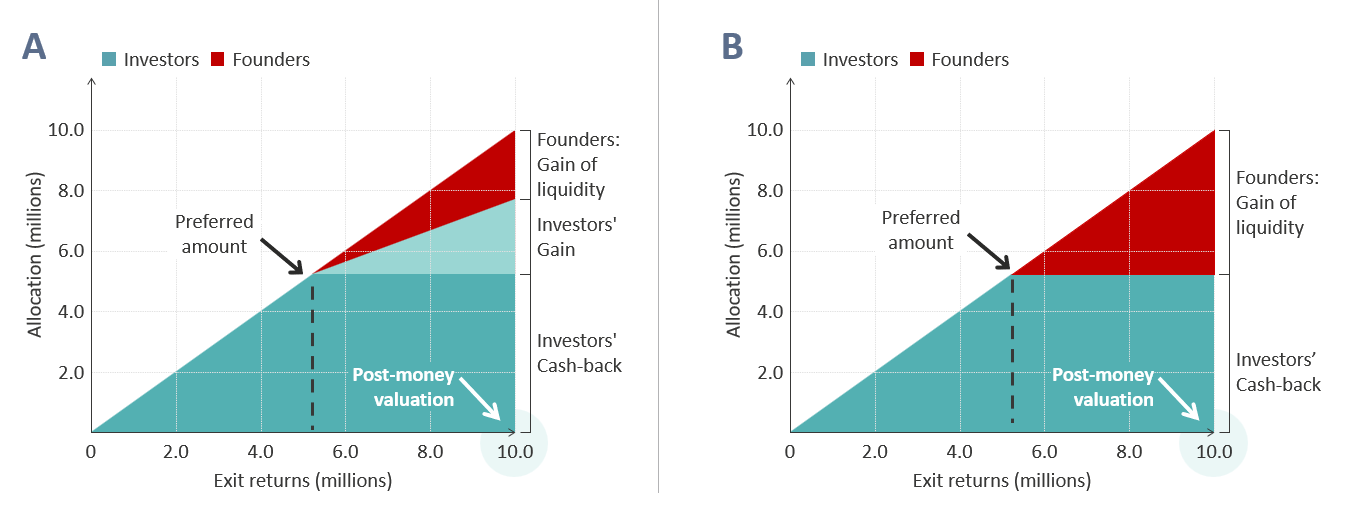

The fundamental principle behind any liquidation preference (LiqPref) is that in a first step investors’ investments (=preferred amounts) are prioritized for payout at the exit event. Such preferred payout is typically facilitated through preferred share classes for investors, ranking senior to the founders’ common shares. In case of several investment rounds, multiple preferred share classes may be implemented, and payout schemes typically follow a LIFO-pattern (last-in-first-out), where the last paid-in money represented in the highest-ranking preferred share class is paid out first followed by payout to holders of lower ranking classes. This payout schedule is indifferent for the two versions of liquidation preference to be discussed. In the example (Fig. 1), after the invested (=preferred) amount of 5 million is initially paid to the investors, additional exit proceeds are distributed under either the participating or non-participating LiqPref.

Participating Liquidation Preference

Under participating LiqPref, proceeds exceeding the preferred amounts are distributed to all shareholders in proportion (“pro rata”) to their shareholding, regardless of the prior return of their preferred amount. For example (Fig. 1A), with 10 million exit proceeds available for distribution, the investors first receive 5 million, and in a second step 5 million are distributed pro rata (i.e., split in half) between the investors (receiving a total of 7.5 million) and the founders (receiving 2.5 million).

Non-Participating Liquidation Preference

The non-participating LiqPref takes into account the already allocated preferred amounts in the pro rata distribution of the second step (Fig. 1B).

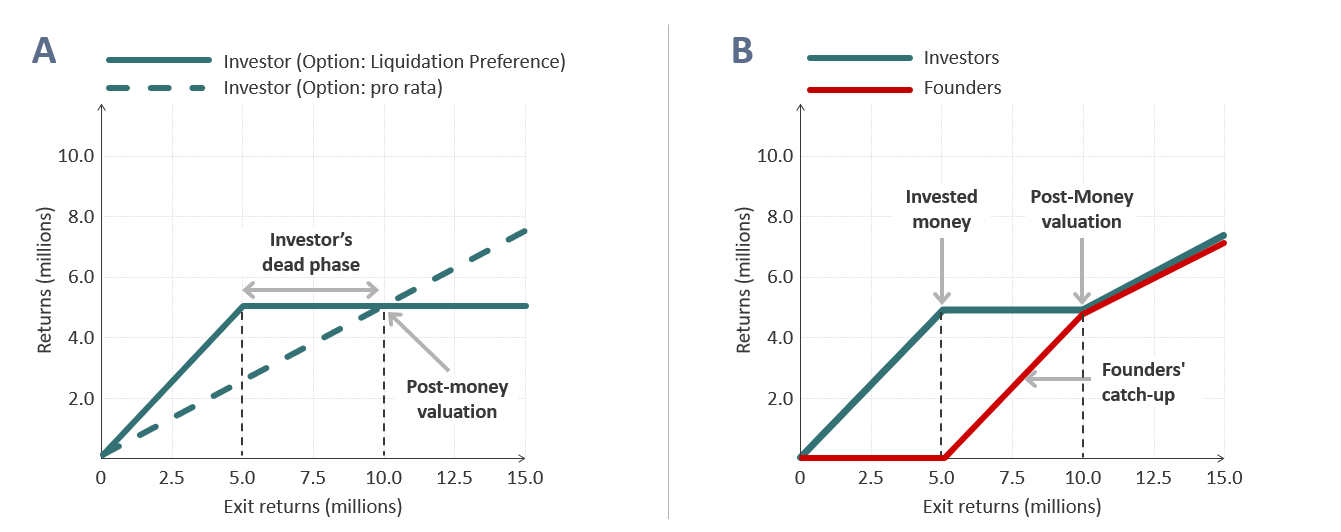

In order to find the correct allocation for investors under the non-participating LiqPref, two calculations are performed: investor shares treated as preferred with LiqPref (Fig 2A, solid line) and as common without (Fig 2A, dashed line), respectively. The higher of the two values is applied. As shown, in a certain range (the so called “dead phase”) investors thus do not participate in the payout, while all exit proceeds exceeding the preferred amounts are confined to common shareholders (i.e., founders) who catch-up their allotment up to the point where the preferred investors are better-off being treated as the common shareholders (Fig. 2B). Generally, this point is reached at the last post-money value, in our example at an exit value of 10 million, where each party receives 5 million.

In case of several investment rounds, the switch from protected to pro rata payouts for investors occurs at different exit values for the different share classes. Therefore, one has to determine which of the share classes are still in the dead phase at a given exit value. Again, the point from which all preferred (=investor) shareholders are treated like common shareholders corresponds to the post-money value of the last financing round.

Balancing interests of founders and investors

LiqPrefs are particularly relevant in the context of anticipated low returns at exit. We like to discuss the impact of these LiqPrefs on the perceived fairness of exit gains for founders and investors. Under non-participating LiqPref (Fig. 1B), is the distribution of the exit proceeds fair? One might argue that it is fair, if the initial contributions of both parties are considered of equal monetary value. In the example, the pre-money value is equal to the invested cash amount (5 million each). However, the contribution of the founders at the time of the financing is in non-liquid assets, consisting of research data, intellectual property, a business plan, management team, etc. From the founders’ point of view, an exit at the post-money value is already a gain, as the initially illiquid assets become liquid. They receive the same amount of cash as investors. In contrast, from the investors’ point of view, nothing has been gained if the value at exit is the same as the post-money value at the closing of the investment round. So, investors merely receive their money back with no reward for the risk they have taken, including the risk of total loss.

In fact, founders are incentivized to even accept low exit values/multiples as their illiquid asset transforms into cash, while investors only gain if exit values significantly exceed the last post-money value, reflecting value creation.

We argue that the participating LiqPref (Fig. 1A) more effectively balances fairness between investors and founders. In this arrangement, the upside for both investors and founders aligns as soon as the exit proceeds exceed the preferred amounts (5 million). From this point onwards, both the investors start to make some profit on their investments, and the founders start to cash in on their previously illiquid assets; a win-win situation.

Although non-participating LiqPref is often perceived as founder-friendly—particularly if the founders are focused on maximizing gains regardless of investor interests—participating LiqPref is generally viewed as more investor-friendly. However, as demonstrated, we argue that the participating LiqPref offers a more balanced approach, reflecting the spirit of a considerate joint endeavor between founders and investors.

Our analysis has emphasized the investor’s need of protection against scenarios with low exit values/multiples. At higher exit multiples, the qualitative difference of the initial contributions, cash by investors and illiquid assets by founders, diminishes, and the applied type of LiqPref becomes less relevant. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue, that from a certain threshold of higher exit values, the right for liquidation preferences should be dropped. In a further publication, we shall elaborate that introducing such cut-offs often comes with unexpected glitches.